How To Grade A Baseball Card: Everything You Ever Wanted To Know

The proper grading of a baseball card is perhaps more difficult than the task of successfully hitting a small, round ball with a long, cylindrical piece of wood three times out of ten. There are so many things that go into grading that it takes time and experience to become an expert in determining the condition of a card. This skill is important because the price of a card is largely determined by its grade. The problem is that there are so many different criteria, each independent of each other yet acting in concert, that small differences of opinion can cause wide variations in the grade, and hence the price.

The very first, and most important consideration in card grading is that condition is completely independent of age. It is also independent of other similar cards. For example, you may own an old card, say a 1957 Topps that is in pretty good shape considering it is almost 60 years old. With a piece of cardboard that old you can expect some corner rounding and loss of surface gloss, maybe some browning of the edges. But the age matters not. If the corners are rounded and there is a wax stain on the back, the card is not mint -- even if the condition of your specific card is far better than similar examples on the market. In other words, grading is absolute, not relative to any other card or year examples.

The second most important consideration is that grading is intrinsic, not sentimental. Though sentimentality may affect the price you are willing to pay, or sell, a card, a crumpled corner is a crumpled corner. Granted, there are many criteria which affect the price of a card, among them demand versus supply, year of issue, manufacturer, relative scarcity of a specific card compared to the others in the series (called short prints,) rookie or star status, and regional fan considerations, but grade has nothing to do with those issues. Or rather, the determination of condition is not affected by other price considerations, but rather the price is influenced by the grade. Card grade is one of the few absolutes that transcends personal whims, distribution patterns, or print runs.

Finally, the last quality of grading involves the individual aspects of the parts being graded. Grading cards involves far more than just looking at a card as a whole and stating that it is pretty clean and nice looking. That may be the impression of an overall glance, but actual grading takes into consideration many facets of the card. Here is a list of the individual items that are considered when grading a card. I will further discuss each item individually throughout this article.

Corner condition

Edge condition

Surface condition

Surface gloss

Color intensity

Image registration

Image quality

Printing quality

Centering

White intensity

Special effects

Before we delve into these items individually, let's first discuss what is a baseball card, or rather the technical aspects of some ink applied to a piece of card stock that becomes a collectable.

Just how is that card made?

Most baseball cards start out as a sheet of card stock. I say "most" because other materials have been used at times, most notably plastic and occasionally metals. But for the most part, the card you hold in your hand is a form of paper derived from trees.

Baseball cards are not just thick sheets of paper, though. They are actually made up of several layers of thin paper glued together. This process ends up with a product we commonly refer to as cardboard. In fact, if you were to take a baseball card and turn it so that the edge is facing you, you can actually take a sharp-edged pair of tweezers and pry those layers apart like an onion. If you do so, look at the separated insides under magnification. You can clearly see the fibers of the wood that went into making the paper. Sometimes the cardboard is brown when it is unbleached, or white when it has been bleached and dyed. But regardless of its color, it is cardboard -- layers of thin paper glued together.

Most often that paper is coated on one or both sides. This coat, applied directly to the cardboard, can be made of a number of different chemicals, binders, and color enhancers. The coat acts to provide a more stable surface to print upon and enhance the surface appearance of the card. It also acts to protect the underlying paper so that the fibers do not fray over time. Think of it as a sealant just like what one would put on a driveway -- a thin layer designed to protect the underlying asphalt. The coat on a card is also sometimes referred to as enamel.

On the coat goes the ink. Though there are many different technical processes involved in applying ink to paper, they all boil down to laying down four colors -- cyan, magenta, yellow, and black -- to a piece of material so that the colors blend to form other colors which make up the intended image. The way those colors are laid down within specific tolerances is called registration. For instance, if you have a black line that acts as a border for a red field, the black line needs to align exactly with the edge of the red ink. If it does, then the printing process is said to be in registration. If it is not, if there is a gap or the black line is superimposed on the red field, the image is said to be out of registration. (Note that out of registration issues are different than out of focus issues. I will discuss this further later.)

Finally, a thin layer of shellac or other clear material (like UV resistant plastic) is applied once the image has been printed on the coat. This is referred to as the gloss. The gloss protects the image from damage that may occur during normal handling and acts to protect the integrity of the ink, maintaining its intensity and preventing color fading. As is clear with older cards, gloss doesn't always work perfectly in preventing those problems.

One important thing to note here is that all the materials, the paper, bleaches, inks, dyes, binders, glues, plastics, coatings, and other materials which go into creating a baseball card are made of chemicals. All chemicals are susceptible to damage from an number of different sources. Paper absorbs water and the glue which binds the fibers is water-soluble. Keeping a card in high humidity will cause it to absorb water and fall apart bit by bit. Not only does the water absorption cause damage itself, but water will combine with chemicals in the paper to create an acid. Paper does not like acid; acid will degrade paper over time. Inks are prone to fading in the presence of ultraviolet light whether from the sun or fluorescent tubes. That fading is actually a chemical breakdown (or modification) of the substances which provide the color to the ink. Shellac coatings can decompose in heat or if exposed to oil such as the oil that occurs on your fingertips.

So now that you have an overview of how a baseball card is made, let's look at how it can be constructed with errors or damaged, and how those errors and damage determine the grade of a card.

Here is the single most important thing to remember about grading baseball cards:

There is no perfect card.

Every baseball card ever made has a problem. No printing process other than that used by the United States Treasury can ever lay down ink in micrometer tolerances. No ink is ever laid down in perfect uniform density and color. No paper is ever created absolutely uniformly. No image is ever perfectly in focus. No cutting process ever exactly separates the individual cards from the sheets they are printed on with perfect centering. No gloss is ever applied in a completely even coating without a single flaw. Ever.

If you take what appears to be a perfect card and place it under high enough magnification all those flaws will stand out like mountains rising from a desert plain. It's kind of like looking at your face in a magnifying mirror; you look great in the bathroom four feet away from a flat mirror, but you are a hideous creature in one of those makeup mirrors like women use to intentionally find serious flaws so they can mope around feeling like Quasimodo on a bad hair day.

In grading cards, we use three different magnifications: naked eye, 4X, and 10X. We also use two three different inspections: cursory, close, and intensive. Let's look at the various types of inspections first.

A cursory inspection is one in which you hold the card 15 to 20 inches from your eyes and quickly look for flaws. At that distance, and with a quick scan, a card may appear perfect, but in reality may possess many flaws. The corners may look perfectly square, but actually be a bit frayed or crumpled. Registration may look perfect, but actually be slightly out of alignment. The surface gloss may appear even and complete, but there may be a minor wax stain or ply dimple on the surface. The color intensity may look great, but it has actually faded slightly, though evenly, so that it looks just fine. There may be one or two tiny ink spots or dropouts that are not immediately noticeable since they are so small. Problems that show up under a cursory inspection generally limit the maximum grade a card can attain regardless of other issues that show up under close or intensive inspection. A rounded corner is a rounded corner; the only other determination will be the degree to which it is rounded. Further inspection of cursory examination involving what presents as a naked eye problem can only downgrade the card, not raise its grade higher.

A close inspection involves literally bringing the card closer to your eyes, though still without artificial magnification (other than standard reading glasses used, if needed, to bring close objects into natural focus.) The card is placed 4 to 6 inches from your eyes and each individual aspect of the card is carefully looked at. That ply bubble that was not noticed under cursory examination is now clearly seen. That corner which appeared to be a perfect cut now shows some very slight rounding or ply separation. That edge which at first glance seemed to be intact shows some chattering, or little flakes of the coating chipped off leaving a slightly uneven edge. The color in a team name printed inside of a black border may not perfectly line up leaving a slight gap not initially noticeable. Turning the card so that overhead light reflects off the coating may reveal not only scratches in the coat, but some of the coat may be thinning out or missing altogether.

For an intensive inspection, I drag out the magnifiers. I use three different magnifying lenses. The first is the magnifying light. These are what you see on workbenches and consist of a largish lens surrounded by a fluorescent tube for light. The assembly is mounted on an articulating arm allowing you to swing it around or out of the way. The magnifying power of the lens is about 2X. (And I am not going to get into a physics discussion regarding diopters, optical magnification, and other arcane aspects of classical optics here. Let is suffice to say that a 2X lens makes the card look twice as big at any given distance.) The relatively low magnification along with the light allows you to easily view the entire card as a whole.

The second magnifier I use is called a dome magnifier. It is 2.5 inches around with one flat side and one rounded side. It is made of a lucite plastic. The dome magnifier runs about 2X to 4X, or again, making the card and its components appear two to four times as large as they do to the naked eye. For a 2X view, it is placed flat on the card (or the card contained in a protective sleeve) and gently moved across the surface to look for problems. Always keep it clean and never drag it around; gently lift it and replace it on the area you are interested in looking at. Just be careful that any flaw you detect in a sleeved card is actually on the card itself and not the sleeve. By raising the dome an inch or so from the card, you obtain a 4X view. Using a dome magnifier allows you to closely inspect about one-tenth of the card surface at a time.

The third magnifier is called a jeweler's loupe. This is a multi-lens optical magnifier that enlarges what you are looking at by 10X. (By comparison, the average makeup mirror noted previously has a magnification in the 4X to 5X range.) A loupe is relatively small, able to fit inside a one-inch cube holder, and is manufactured with greater optical precision than the other two types of magnifiers. You hold the loupe about one inch from your eye and the card about one inch beyond the loupe. This allows you to magnify enough to actually see clearly the paper fibers and the individual dots of ink which go into making up the image. A loupe inspection looks at about 1/80th of the card surface with each view. As you can see, when I say "intensive," I mean intensive. Every aspect of the card is given close scrutiny. All four corners, the edges, surfaces (both front and back) the registration of finer details, and the application of the inks across the surface. Placing a card under successively greater magnification and detecting no flaws as one runs up the magnification scale only increases the grade of the card.

So now that we have discussed the basics of how a baseball card is constructed and how to look for flaws, just what are these grades everyone talks about?

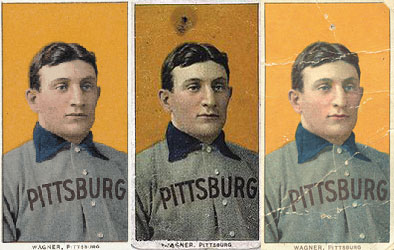

Grades are nothing more than an artificial scale by which one can denote the condition of a card. It is important to note here that it is not legitimate to simply delineate specific aspects of a card, assign a number to them corresponding to the level of degradation, then add up the numbers to assign a grade. Though each individual type of problem can be assessed and placed on a scale, the grade is determined not only by the specific numerical scales, but by the overall presentation of the card. Assigning numbers to specific issues only allows one to communicate in text the issues that went into assigning the final card grade. Confusion arises in grading by companies placing a numerical value on the grade of a card as if that number is some sort of composite. It is not. That number is (or should be) merely a shorthand method of announcing a grade, generally on a scale of 1 to 10, or 1 to 100, with 100 being that quintessential "perfect" card and 1 being something suitable for use as kindling in a fireplace. As such, the numerical scale is relative to "perfection" as a standard. I have to add, though, that if I owned a T206 Honus Wagner in poor condition, I would not use it as kindling. Some cards have significant value independent of their grade. A 1991 Fleer common would, however, be starting some fires in the wood stove. (I'm convinced that someone, somewhere, is still printing them.)

But the scale is also roughly logarithmic. At the upper end of the scale, minute changes in the presence and severity of flaws create huge differences in the grade. While at the lower end of the scale, large differences may only move a card one grade downward. Also the finer the grade distinctions, the more subjective the grading process becomes when trying to determine which exact grade level a card belongs in. With all that in mind, remember that a grade is just a general indication of what the condition of a card is, and only then when all parties are on the exact same page as to what each specific grade represents.

So what are these grades?

They are as follows, with their abbreviations in parentheses along with the numerical grade generally assigned on both the 1-10 and 1-100 scale.

Pristine Mint (PM, 10, 100)

Gem Mint (GM, 9.5 or 10, 98)

Mint (M, 9, 96)

Near Mint/Mint (NM/M, 8, 92)

Near Mint+ (NM+, 7.5, 88)

Near Mint (NM, 7, 84)

Excellent/Near Mint (EX/NM, 6, 80)

Excellent+ (EX+, 5.5, 70)

Excellent (EX, 5, 60)

Very Good/Excellent (VG/EX, 4, 50)

Very Good (VG, 3, 40)

Good (G, 2, 30)

Fair (F, 1.5, 20)

Poor (Poor, 1, 10)

As you can see, a two point difference at the top of the scale drops the card one full grade. The next grade drop is also two points. Then it changes to four points for the following four grades, and finally ten points for the lower grade differentials. Again, tiny differences make big differences at the top of the scale. Though different grading services have slight variations in their scales, they all cluster around those general grades and numbers.

Let's now go back and look at the areas of a card which are subject to grading. Again, they are:

Corner condition

Edge condition

Surface condition

Surface gloss

Color intensity

Image registration

Image quality

Printing quality

Centering

White intensity

Special effects

I'll now define and review them one-by-one indicating what they would look like on that perfect, non-existent card. Remember, these characteristics are what you would find in a card that is truly perfect, grading at a 10 or 100 depending on the scale. Also remember that such a card does not actually exist regardless of what number a grading service may put on the slab encasing the card.

Corners: A corner is the spot where two adjacent sides of a rectangle or square meet. There are generally four of them per card, though some cards may have three (when shaped in a triangle,) many corners (such as the Topps Laser issue,) or anything in-between. A few issues were even round. Perfect corners are just that -- perfect. They meet at an exact 90 degree angle. They have absolutely no rounding, fraying, ply separation, enamel separation, compression, or dings.

The condition of the corners, along with the centering of the image, are the two most important things an average collector will look at, even though all the other factors go into properly grading a card.

Edges: The straight portions of the card connecting two corners. Again, some cards may not have straight edges by design such as the round issues or cards with intentionally curved sides or corners. But if it is supposed to be straight, it better be dead straight. No chattering, no tearing of the enamel, no feathering, no rubber band puckers, and no nicks.

Surface: There are two surfaces on each card -- the front and the back. The front of the card is generally where the image of the player is located, while the back is where you find the player statistics. When discussing surface condition, you are only considering the underlying materials that make up the card and not the printing contained on or under those materials. The surface must be completely even with no ply bubbles, scratches, tears, enamel wrinkles, or imperfections caused by substances such as water, wax package deposits, or gum residue. There will be no dimples, or pinholes as some people call them. Those are tiny depressions as if someone took a sharp pin and gently poked the surface. Creasing is also a problem with the surface. Creases are simply bends in the card. Some creases are so fine that you have to squint to see them. Others are huge and resemble the Grand Canyon. A perfect card doesn't even have an inconspicuous crease caused by two layers not meshing properly, let alone an actual bend.

Gloss: Recall that the gloss on a card is a thin layer of shellac designed to protect the underlying image from environmental damage as well as to give the card a reflective sheen. A perfect card has a completely even application of gloss without apparent thickness variation across the face of the card. There are no bubbles, minute debris entrapped in the gloss, or abrasive thinning. The entire gloss on a perfect card is still completely clear and shiny, not having undergone any chemical degradation that would alter the color in any way, generally resulting in a yellowing or browning of the shellac. Another thing to consider is little flecks of missing gloss that may even extend to the ink of the image. In the 1990s, baseball card manufacturers changed the gloss they were using. When that new gloss got warm as it might in a warehouse, it got tacky. Then the cards stuck together. When you try to separate the cards, the tension causes damage to the front and back surfaces of both adjacent cards. I have seen 1998 Topps sets that come out of a factory box looking like a solid brick and can not be separated no matter what you do.

Color: This is where things can get tough. What was the original intent of the card designer and printer as to what the exact color should be and the density of that color? The 1986 Topps is a perfect example of this. The intent was that the black background that bleeds to the edges be intense and deep black. There is significant variation, though, in just how black the black actually is. Many cards have a slight grayish cast to them, while others look washed out. Hue matters as well. Exactly what shade of red was intended? Does the card you hold reproduce that red faithfully, or is there a tinge of orange or purple, sometimes almost imperceptible? Is the blue intense, or does it almost resemble a pastel? The only way to answer many of these questions is to know what the colors are supposed to be in the first place.

Some determinations are easy -- what orange is used in the official Mets logo and is it faithfully reproduced on the card? What color is a player's skin tone and does the image on the card look like it matches that skin tone reliably? It is more difficult regarding arbitrary colors such a backgrounds. Sometimes you just have to wing it, but always presume that the designer intended the color to be appropriately perfect for the graphic layout of the card. If you really want to lose you mind, try grading color on the 1990 Topps base set. I think the graphic artist had way too much fun with recreational drugs back in the 1960s.

Registration: Is all the ink exactly where it is supposed to be? A perfect card has each of the four colors imprinted in the exact location they were intended. In an orange spot, the red and yellow align exactly as intended such that there is no slight red or yellow rim on the image. A hairline is placed exactly on the border of the section it is supposed to delineate. Are each one of those colored dots laid down in the exactly right spot so that the eye perceives an intermediate color as intended, or do the dots of one particular color obscure another set of dots causing a color shift?

Image quality: And no, I'm not talking about how good the picture is, whether it captures the essence of the player or the moment. I'm talking about things such as focus. Is the focus of the image sharp and clean? One would presume that any photograph intended to be used on a card was in-focus on the negative itself. An out-of-focus issue arises in the actual compositing of the image intended to be printed on the card. Are the details sharp and clear? Can you see individual hairs in a player's mustache?

Remember, proper focus deals only with the object of the picture, not the background. Many photographs are taken so that the background is intentionally out-of-focus to create an effect of depth. Also consider that some images are intentionally blurred to give the effect of motion. Again, go to the intent of the photographer and try to determine if that intent was properly transmitted to the final product by the graphic layout and printing process.

Printing: The perfect card has an even application of ink in exactly the areas that ink is supposed to be located. There will be no drop outs (or missing spots where ink was not deposited,) no blobs (spots where ink was deposited and was not supposed to,) printing lines (streaks of ink caused by trailing ink in the printing process,) smears, flecks, spatterings, or white pips (little specks of white ink.)

Centering: Centering is measured as a percentage and expressed as 50/50 on a perfect card. In other words, when you look at the top border with respect to the bottom border, and the side borders with respect to each other, the image is perfectly centered such that both pairs of borders are the exact same width around the central image. A 65/35 means that one border is twice the width of the other. A 75/25 border means that one side is three times the width as the other. A 90/10 means that one side is nine times the width.

On many cards, this determination is very easy; the image of focus is itself surrounded by a box composed of hairlines. Just look at the distance between the hairlines and the edges. If both opposing borders are the same, then the card is 50/50. Many cards, though, are notoriously difficult to determine centering. Generally, those cards are made up of scenic images where the image bleeds to all the edges and contains no internal borders or reference hairlines. In those instances, you have two choices. One, compare hundreds of examples of the same card, trying to determine which of those cards looks appropriately centered. Then use that one card as your reference example by which all the others are judged. Or two, wing it.

Many times the additional printing superimposed on the image will give you some helpful clues. Study the team logos, player's name, position indicator, and other aspects of the graphic design to see how well those aspects are centered. You also have to be aware of a diamond effect. That involves the card not being cut properly, leaving the image slightly askew, or twisted with respect to the edges of the cardboard it is printed on.

One important aspect of centering you need to understand is that a card which is considered near mint has a centering of 70/30 or 65/35 on the front. That card will actually look noticeably off-center especially when compared directly to one which has perfect 50/50 centering. Yet it is still near mint.

White intensity: This is a measure of how white is the white. Unlike colors which have a specific hue that changes depending on the ink mix, white is white. It is the absence of all color. Perfect white reflects 100 percent of all wavelengths which strike it. By reflecting all colors, no color is dominant and we perceive the area as white. But there are different whites like ivory, cream, and other slight tinges of color that shift the white to a point where it is no longer true white. In reality, no white is ever really true white since no substance will ever perfectly reflect all colors equally. However, there is also a quality called brightness. Do not confuse the two.

Brightness is the percentage of light a piece of paper reflects. A page can be very close to pure white, but not reflect much white thereby appearing somewhat dullish. Or it can be very bright and almost be blinding when viewed in full sun. On a card, degradation of the whiteness and brightness of the white areas can be caused by any number of conditions, among them dirt and grime coatings, chemical changes in the ink, breakdown of the gloss creating a yellow cast, or a mis-formulation of the ink itself. The most common expression of a white problem is the appearance of browning along the edges of the card, making it look aged through exposure. A perfect card retains the original white in the original intensity across the entire card face.

Special effects: That is the term I use for any graphic design or printing application that does not involve the actual deposition of ink. This category includes things such as embossing, chroming, refractor effects, holograms, the application of metallic border effects, gold leaf hairlines or emblems, and other marketing gimmicks, er, graphic design applications. Many of these effects are obvious when they have errors. For instance, when a gold hairline is broken because some of the gold has flaked off. Others are very difficult such as some refractor effects on a one-of-one card. When you only have one example, just what is it supposed to look like. The only real clue you would have is to catch the graphic designer holding the card up to the heavens and shouting, "It is good!"

Now that you have some background on the physical nature of a baseball card, the components which make it up, and the areas of concern when it come to grading, we now get to the ultimate question...

How do you grade a card?

The answer is...who knows?

Wait, let me clarify that a bit.

When grading, you have to have a standard by which to measure all other cards. You can not really use Pristine Mint or even Gem Mint as that standard because very few cards would successfully measure up to that in comparison. When you start getting into the lower grades like Excellent or even Near Mint, flaws start becoming readily apparent and widely varied. I prefer using the definition of Near Mint/Mint (an 8 or 92) as that standard. The definition of Near Mint/Mint I use is:

A card that on cursory inspection appears to be Mint, but upon closer inspection reveals minor flaws not immediately apparent in a cursory look. The corners are going to appear to be clean and sharp. The edges will look straight without imperfections. The image will be centered 65/35 or better on both axes. The color looks good as well as the actual printing. There is a nice sheen on the surface that appears continuous. Once you have made that determination, you then perform that close inspection.

If under close inspection, you still find no discernable flaws (or they are so minor so as not to appreciably affect the card's appearance or presentation,) the card becomes Mint. Then you go to intensive inspection under 4X. If you still can not find any discernable flaws, the card in Gem Mint. Then you pull out all the stops and use 10X. If you STILL can not find any flaws, the card becomes Pristine Mint and, depending on the specific card in review, you may commence making retirement plans.

I think the best definition of what constitutes a minor flaw was written by Kit Keifer and is found in the Sports Collectors Digest book, "Getting Started In Card Collecting" issued in 1993. It states:

"To a buyer, a minor flaw is a teensy-weensey irregularity in the dot pattern you see when you put the card under an electron microscope. To a seller, a Near Mint card with a minor flaw is the minor penetration and slight powder burns left by a blast from a 12-gauge shotgun."

For me, I'm going to call all cards that appear to be Mint on cursory inspection as Near Mint/Mint. I really don't care if they are Mint, Gem Mint, or Pristine Mint unless the particular card is so valuable (or potentially valuable) that intensive inspection will be worth my time and an extended vacation to Fiji upon its sale.

But what about the other direction?

Poor, Fair and Good are easy. A Good card is one which you can use as a filler until you find a better card. A Fair card is one which reminds you of an 85-year old native Floridian who has spend way too much time in the sun and operating room. A Poor card is one in which you have difficulty discerning what it may have originally looked like.

The only other grades I consistently use to describe an individual card are Near Mint, Excellent, and Very Good.

For a Near Mint designation, take a Near Mint/Mint card and slightly fuzz the corners, not appreciably, but make it noticeable if you glance at the card. It looks a bit off-center. The surface is starting to show some wear and loss of that shiny gloss. There may be some printing issues like blobs or dropouts or lines that are noticeable, but do not really detract from the overall presentation of the card. There may be a tiny registration problem, but it is not really noticeable unless you are specifically checking the registration of the images, borders, and hairlines.

An Excellent card has rounded corners that are obvious, but just affect the tips of the corners, and is most definitely off center. The edges may be dinged just a bit or have some chattering that is evident. The image is a bit out of focus and there are some printing defects that are starting to impinge on the presentation of the card. It looks like it may actually have most of its gloss left, though some of that gloss may actually be a wax stain. You're starting to see some yellowing of the edges and maybe some color shifting caused by exposure and not a printing problem. It may have a small crease, but it does not break the surface, nor does it extend more than about an inch or so.

A Very Good card is one in which you can actually see the roundness of the corner, but it doesn't yet look like the arc of a penny. The surface may be scratched or scuffed with spots on the gloss missing entirely. Though it may have a crease, the integrity of the cardboard is intact and the surface is not broken. The card does not feel floppy or mushy when you handle it. It is seriously off-center, but not cropped on either axis. The person responsible for proper printing registration had a couple of beers during lunch before calibrating the press for the afternoon run.

The only time I use an intermediate grade is when I am selling complete sets of cards or lots whose condition varies across the offering. I may have a set of 1973 Topps where a large number of cards are Very Good, most are Excellent, and a handful are Near Mint. I would call that a set ranging from Very Good to Near Mint, centered on Very Good+. If there were more Near Mint cards than Very Good, I would call it a set ranging from Very Good to Near Mint, centered on Excellent+. When I sell a set with only one grade applied, you can be assured that every card in the entire set is at least that grade listed.

So how do the individual components affect grade?

As I alluded to earlier, the ultimate grade of a card is not the absolute composite of its constituent parts. You don’t assign a number to each of the criteria then add them up to get a final grade. A card may be virtually perfect in all aspects except centering which is, say, 85/15 on the front. That card can grade no higher than Excellent simply because the centering is bad. It could have corners as sharp as razors, but that doesn’t matter. Or a card could be perfect except for a bent corner. That card is also no greater than Excellent even though without that corner issue it may be a Gem Mint.

Keep in mind that problems with the different criteria involving cards are subtractive from the ideal. The are not additive. A card can grade no higher than the weakest aspect of its composite.

In cases where a card had multiple problems, it involves subjectivity in determining just how significant each individual problem is with respect to the overall look of the card as to where you place it on the grading scale. For that reason, many grading companies will append a grade with a qualifier. For instance, they may state that a card is near mint/mint but off-center (denoted by OC.) That means the card has clean corners, edges, gloss, is in registration and in good focus, but it is skewed to one side. Personally, I do not think that is valid. It would be far better to represent the card with a grade of Excellent (OC,) but otherwise near mint/mint with the emphasis placed on the problem.

So why grade?

We grade to establish a standard by which we can communicate remotely the absolute condition of a card. With a proper grade, I can be assured that something I purchase is what the seller intended to offer. I have had many people call me to offer collections for sale. I ask them what condition the cards are in and they say “great.” That means nothing to me since “great” is not a proper grade and their idea of “great” is most likely relative to the age of the cards. Don’t ever forget, grades are absolute, not relative.

Grades are also used to protect your investment. Unless you are dealing with a particularly rare or old card, a drop in even one grade can affect not only the price you should pay, but also the probability of that card increasing in value over time. I will gladly take a 1933 Goudy Babe Ruth in fair condition. But for a 1989 Topps anything less than near mint/mint is garbage. We literally throw them out. They will never be worth anything let alone appreciate in value.

See, I told you this wouldn’t be easy. But I do hope that you now have a greater understanding of how cards are graded and generally what the different grades represent. Just keep in mind that much of the finer differentiation is a matter of subjectivity and don’t take the splitting of hairs between a card graded at a 91 versus one at a 92 too seriously.

Most Popular

The ULTIMATE

Collection

for the

ULTIMATE

Baseball Fan!

- A complete 41 Year collection of your favorite MLB team.

- Every Topps® standard issue card from 1977-2017

- PLUS Topps® Traded cards, cards with multiple players such as League Leaders, World Series and Future Stars, and all of the rookies from the '90, '91 and '92 Topps® Debut sets.

Choose Your Favorite Team For Detail And Become One Of Our Happy Customers:

"I want to personally thank Steve Crisp in all the hard work he puts into putting together such a fine product as well as thank him for bringing back the joy collecting has brought to me. I am a die hard Mets fan who like many other people collected baseball cards as a kid. I collected from the mid 1980's to the early 1990's because I love the game and I am such a huge Mets fan. As I went through my teenage years I grew apart from collecting cards but always had my love for the game and my team. One thing though that I always wanted to do though is put together a complete and comprehensive Mets Baseball Card collection but for over 20 years that dream was put on hold. 2 years ago I saw this page on Facebook and my thoughts of putting together this collection became renewed. So I jumped in, 2 years ago today. I had the pleasure of talking to Steve as well as meeting him when I picked up my Mets Ultimate Team Set from him (We both ironically live in the same town!). I told Steve what I wanted to do for a collection and he was gracious enough to help me out with complete team checklists and he gave the springboard to start my dream collection. In 2 years, I started with nothing, and bought this collection of 1273 cards. They are so well put together and I can't recommend the product enough to anyone who loves baseball and has a favorite team. Well, today my collection has grown to 6665 cards, no duplicates, all Mets. But I would have never got the ball rolling if it wasn't for my initial investment in my Ultimate Team Set. Thanks again to you Steve for all the hard work you put into putting this great product together and thank you for getting me back into this fabulous hobby again. If anyone out there is looking to but together an Ultimate Team Collection this really is the best place to start! Lets Go Mets!"

New York Mets

(03/29/2016)

"If you are on the fence about making this purchase - get off it and buy it!"

New York Mets

(10/28/2015)

"First Class Seller A+"

New York Mets

(10/22/2015)

"Excellent communication, fast ship, incredible product. Many thanks again."

Toronto Blue Jays

(10/12/2015)

"Fast delivery and great product!"

New York Mets

(10/08/2015)

"Fast & Accurate - Recommended"

New York Mets

(10/01/2015)

"Item as described, excellent correspondence, highly recommend, an asset to eBay!"

Detroit Tigers

(08/22/2015)

"Great seller"

Baltimore Orioles

(08/07/2015)

"Once again, excellent deal. very satisfied. repeat customer, HIGHLY recommend!"

Tampa Bay Rays

(08/01/2015)

"5 Star"

St. Louis Cardinals

(06/20/2015)

Comments